- Published on

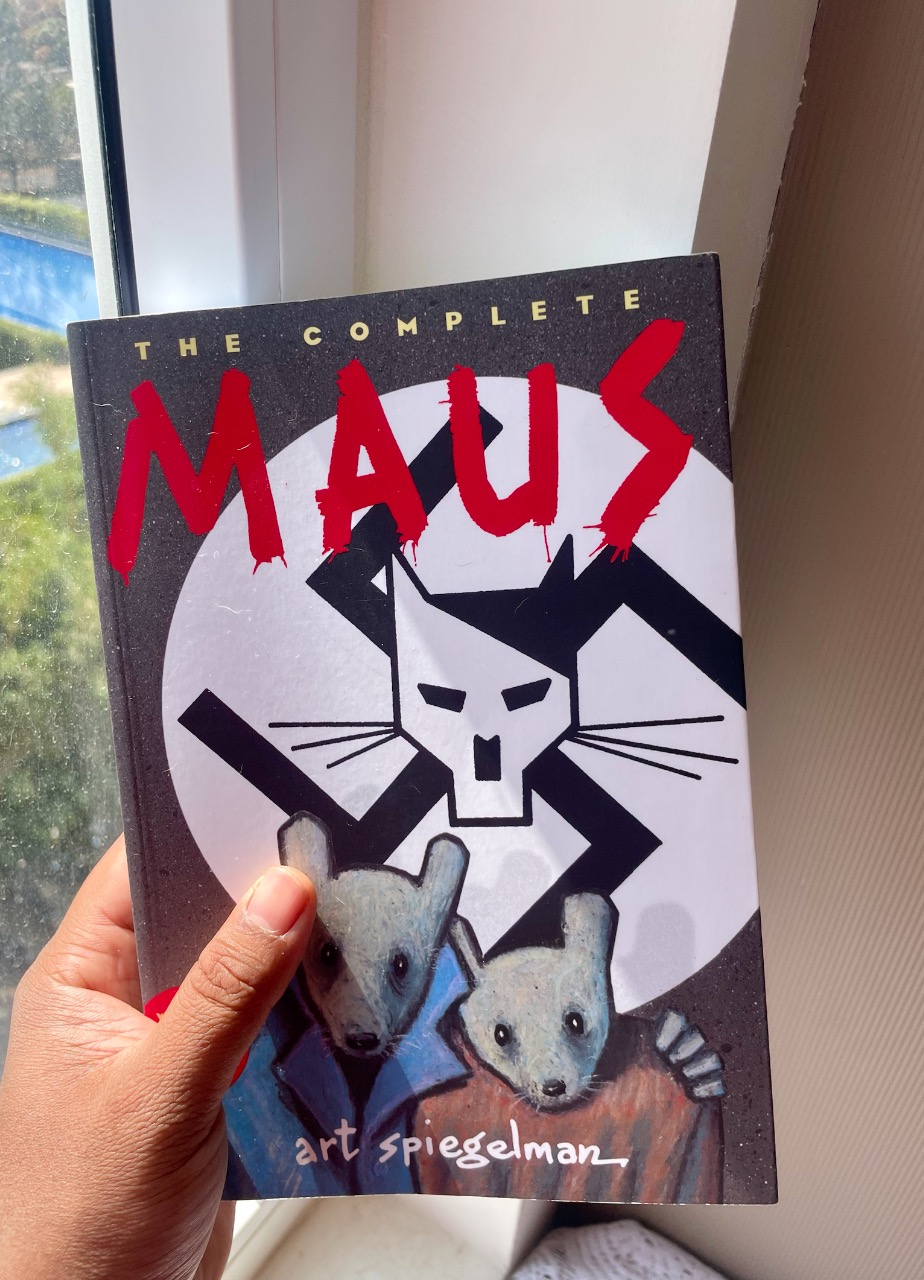

Art Spiegelman's Maus

For someone born and raised in India, the Holocaust always felt distant, almost alien. While millions were being systematically murdered in Europe, we were fighting for independence from the very Britain that opposed Hitler. Our schools never taught us the Holocaust in detail—the focus was entirely on our own freedom struggle. Moreover, Hitler and the Nazis were fighting the Allied forces, which included Britain. Since our own struggle was against British rule, there was an unspoken “enemy of my enemy is my friend” sentiment. As a result, Hitler was never presented to us as the demonic figure he truly was, and the magnitude of his cruelty was largely absent from our collective understanding. What I knew of the Holocaust came secondhand, filtered through books, articles, and especially films like Schindler’s List, Saving Private Ryan, Pianist and other war movies, abstract enough to keep at a comfortable distance.

There was something else, too—something harder to admit. Growing up in a Muslim community, there was a subtle but persistent notion that Jews were “the enemy,” largely shaped by the Israel–Palestine conflict and broader religious and political narratives. Even though my family wasn’t particularly religious, antisemitism existed in quiet, normalized ways. I had never met a Jewish person while growing up. Jews are an extremely small minority in India, with a few communities like the one in Kochi, but we never lived alongside them. There was no lived experience to justify this prejudice - it was inherited, imported, and unquestioned. Because of this ignorance, the Holocaust sometimes felt abstract, or worse, morally distorted as if Jews must have done something to deserve such suffering. Disturbingly, books like Mein Kampf were easily available, and I remember classmates openly admiring Hitler as a strong leader, without any understanding of the atrocities he committed.

This is the ignorance I brought to Art Spiegelman's Maus.

Maus explores the Holocaust through the lived experiences of Spiegelman's parents, especially his father Vladek, a survivor of Auschwitz. Jews are depicted as mice, Nazis as cats, and Polish people as pigs. One of the most striking aspects of Maus is that Spiegelman does not portray his father as a heroic or purely good man. He is deeply flawed—ambitious, money-minded, eager to climb the social ladder. Early on, he comes across as opportunistic, even dumping his girlfriend to marry Anja because she came from a wealthy family. He is morally grey. And even later, despite having endured unimaginable discrimination himself, he still harbors prejudice against others, especially Black people. That contradiction is uncomfortable, but profoundly human.

As the chapters unfold, we see how society’s attitude toward Jews changes slowly and deliberately. People become distant, hostile, and unwilling to engage with them - neighbors, classmates, business partners alike. It was not sudden violence; it was calculated, normalized exclusion. That gradual progression felt especially relevant in today’s political climate in India, where similar patterns of majorities marginalizing minorities can be observed. Maus shows how such horrors can happen anywhere, when hatred is nurtured, stereotypes are weaponized, and exclusion becomes routine.

Over time, Jews are pushed out of everyday life, cut off from social spaces, businesses, politics, and even basic human celebrations. Then comes forced labor, extreme hardship, and finally, systematic violence. The depiction of Auschwitz -the camps, the gas chambers - is horrifying beyond words. The cruelty is relentless, absolute, and deeply disturbing. Some of the violence described feels almost unreal. It’s hard to comprehend how people could do such things to fellow human beings. How does hatred reach that level? Is it something unimaginably complex, or is it terrifyingly simple, something that can be planted, nurtured, and normalized in individual minds and entire communities? Maybe I’m naïve but that disbelief is precisely what makes the Holocaust so terrifying.

Beyond history, Maus is also about a deeply strained father–son relationship. Art’s father disapproves of his career as a comic artist and is portrayed as miserly, controlling, and emotionally suffocating. His frugality borders on obsession. Art’s mother, Anja, eventually commits suicide, and Spiegelman includes a comic within the comic to process that loss. It is devastating - raw, honest, and beautifully restrained in its art.

Finally, Maus raises unsettling questions about children who grow up in the shadow of their parents’ suffering. There is a form of inherited survival guilt -a constant sense of gratitude that becomes a burden. These children live with stories of pain so immense that their own struggles feel illegitimate.

Maus is not just a book about the Holocaust. It is about memory, guilt, inheritance, prejudice, and the terrifying ease with which humanity can lose its moral compass. It is uncomfortable, exhausting, and an essential read.